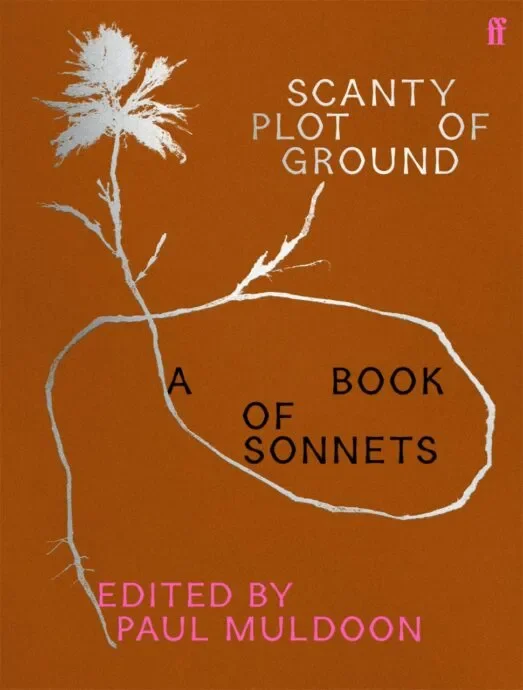

SCANTY PLOT OF GROUND: A BOOK OF SONNETS, Edited by Paul Muldoon

In the sparsely attended centuries-long foot race of fixed poetic forms in English, the sonnet has clearly left its competitors in the dust. Sestinas put on a spurt a few decades ago, and one encounters an occasional villanelle and even a rondeau in the magazines, but it is hard to imagine a cycle of any such thing winning a Pulitzer prize in the 2020s, as Diane Seuss’s frank: sonnets did in 2022. Of course, as Matilda Sykes points out in her recent review (TLS, August 15, 2025), Seuss’s aren’t your grandfather’s sonnets. Made up of free-roaming rhymeless lines, each is “a house […] burst open, windows and doors swinging on well-oiled hinges”.

Ramshackle digs, purists would call them – signs of a neighborhood in decline. Yet one can still see the good old bones beneath the peeling plaster. Seuss’s lines may be unmetered, but there are fourteen every time, with at least a hint of a volta midway. Besides, she was far from the first to modify the traditional structure to her specifications. As Paul Muldoon points out in his coolheaded and evenhanded introduction to his excellent new anthology of sonnets, Scanty Plot of Ground, Black American poets in particular have long pushed at the walls of “pretty rooms”, be it thematically, as in the case of Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die” (“Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!”), or structurally, as in the works of Wanda Coleman and Terrance Hayes, whose freer “American sonnet” form “may indeed be ‘part prison’ but it is a prison with a recreation yard – perhaps even a sequence of interconnected recreation yards”.

That said, it would be inaccurate to claim that Coleman’s extension of the sonnet to sixteen lines, for instance, was unprecedented. George Meredith had beat her to it by a century with his Modern Love (1862). Muldoon doesn’t include any entries from that sequence in his book, nor does he choose any of Gerald Manley Hopkins’s three “curtal sonnets”, instead representing those two masters with, respectively, “Lucifer in Starlight” and “The Windhover”. Yet these two treatments of sudden descent exhibit their own lapses from the Petrarchan ideal. The strong narrative volta in the Miltonic “Lucifer” comes just before the final couplet, when the subject is confronted by the sight of the Almighty’s perfectly arranged stars (that “army of unalterable law”), while the sprung rhythm of “The Windhover” comes as a bracing shock to the reader who sees, on the facing page, the neat iambic pentameter of Surrey’s “I never saw you, madam, lay apart”.

Then again, the sonnet preceding the “The Windhover” is Robert Herrick’s “Delight in Disorder”, which not only employs tetrameter in place of the usual pentameter but also, appropriately enough, throws in a few enlivening substitutions for iambs, so as not to be “too precise in every part”. As the cavalier poet reminds us elsewhere, “Numbers ne’er tickle, or but lightly please, / Unless they have some wanton carriages”.

The pleasures of Muldoon’s superb selection are anything but light. He wisely chose to arrange the 124 works, composed over some four centuries, alphabetically by author surname. This allows us to appreciate how much variation the sonnet has withstood since it was first imported into English, via loose translations from Petrarch, by Thomas Wyatt. Withstood is the wrong word. The sonnet has thrived precisely because it invites variation; its very structure of proposition and resolution demands a turn of mind, and that turn often inspires poets to twist the mold that contains it, so that the form can mirror or reinforce the content. The twists needn’t be seismic. Consider the metrical distress of the second line of the sonnet excerpted from Marilyn Nelson’s magnificent, moving cycle for the stuttering fourteen-year-old victim of a lynching, which derives its effect by departing from a largely regular base: “Emmett Till’s name still catches in my throat / like syllables waylaid in a stutterer’s mouth.”

Such departures – and more radical ones, too – are only meaningful if the reader retains a sense of where the boundaries are, and Scanty Plot of Ground is full of reminders. Not only do most of the poets at least in large part abide by Petrarchan or Elizabethan rules (with the recently departed Tony Harrison sticking close to the Meredithian sixteen-line model in his quietly piercing “Long Distance II”), but we even get a primer, albeit in unruly verse, from Billy Collins’s “Sonnet”: “All we need is fourteen lines, well, thirteen now, / and after this one just a dozen …”. Other self-referential sonnets, including Robert Burns’s “A Sonnet upon Sonnets” and Wordsworth’s “Nuns fret not at their convent’s narrow room”, from which the book’s title is taken, pepper the pages. My personal favorite of these is Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “I will put Chaos into fourteen lines”, in which the speaker holds the personified mess of her life “in the strict confines / Of this sweet Order, where, in pious rape” he is reduced to “nothing more nor less / Than something simply not yet understood”. It is as if Yeats’s Leda, whose appearance in “Leda and the Swan” closes Muldoon’s selection, had turned the tables on the divine Swan, pinned him down and forcefully “put on his knowledge with his power”.

Surveying the possible reasons for the sonnet’s runaway success in his introduction, Muldoon touches on the form’s mathematical perfection (the octave and the sestet are, as some have claimed, “an embodiment of the Golden Ratio”) and the impression it creates of “observing the thought-process of the speaker […] to such an extent that what we’re engaged with is not a poem at all but a form of drama”. In the end he comes back to the drama of form – to the sonnet’s irresistible tug of war between Chaos and Order, rule and departure, “grave restraint and giddy release”. The sonnet, he writes, “is a room which we may make our own while being simultaneously mindful of, and oblivious to, the other guests who have occupied it over the centuries”.

That, too, is one of the pleasures of his selection and arrangement. Echoes and homages abound. Turning the page on John Milton’s “When I consider how my light is spent”, for instance, we find Edwin Muir’s “Milton”, in which the poet restores his predecessor’s sight: “A footstep more, and his unblinded eyes / Saw far and near the fields of Paradise.” While we’re on the M’s, it would not have been excessively self-serving for Muldoon to have snuck in one of his own brilliant sonnets, like “Extraordinary Rendition” or some of “The Old Country”. Instead, he provides us with his own fresh translations of poems by Charles Baudelaire, Rainer Maria Rilke and César Vallejo. The sestet of the Frenchman’s “Correspondences”, in the editor’s handling, will give readers a fair sense of this anthology’s pungent variety:

Some of those perfumes are sweet as a baby’s pelt,

oboe-bright, green to that distant horizon;

others are quite funky, fly-blown, beating a big drum,

building as all illimitable things must build –

the amber, musk, frankincense, and gum resin

giving voice to the soul’s throb as to the body’s thrum.

Boris Dralyuk, TLS